This is what you call starting with a swagger:

.

If the postman who served the southern side of Belgrave Square that summer had not been a 'lewd fellow of the baser sort', many things might have panned out differently.

It is doubtful if Diana Duncannon would have met a certain distinguished foreigner who was then visiting London. Swithin Destime might have terminated his career, unusually brilliant to that date, as Chief of the Imperial General Staff. The life of an elderly Russian lady, then living in Constantinople as a refugee, might have been considerably prolonged, and a number of other people might not have had the misfortune to lose theirs in the flower of their youth. The Turkish Government would have found itself - but there, the postman was a 'lewd fellow of the baser sort' and, strange as it may seem, it is just upon such delicate matters as the glandular secretions of postmen and their moral reactions to the same that the destinies of human beings and the fate of nations hang.

.

So, just how do you follow The Devil Rides Out?

Do you attempt some bold new change of direction? Do you labour over a sequel that you hope will be twice as good but which will probably just be twice as long? Do you retreat into two years of indecision before daring to write again, only to have the new work tepidly received? Or do you get straight back in the saddle and come out blazing with a back to basics, business as usual barnstormer?

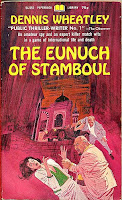

Wheatley, no surprise, chose the latter course, and re-entered the fray with a tale of political intrigue, exotic locales and dire peril: The Eunuch of Stamboul. It is a novel in the grand Wheatley tradition, a return to the meat and potatoes espionage thriller that he had not attempted since Forbidden Territory, and yet another unqualified success.

.

It also makes for fascinating reading just now, since its central question - whether Turkey will embrace Western modernity or retreat into Islamist medievalism - is as relevant as ever, especially in the light of current debates over the country's fitness or otherwise for EU membership.

The action is set against the background of Kemal Ataturk's modernisation drive, which enforces religious freedom through political coercion, and concerns the planned insurrection of a group of starry-eyed jihadists who yearn for the liberty of theocratic enslavement.

This is the very paradox consuming the Middle East today, and Wheatley's commentary on it, as surprisingly even-handed as it is characteristically robust, makes for a genuinely timely read. The pleasures of a Wheatley novel are usually to be found in the remoteness of their mores and concerns from modern life, and the insight they offer into the everyday concerns of generations past. The excitement here, by contrast, is to be found in how bizarrely contemporary so much of its backdrop seems.

At first he seems foursquare on the side of the Islamists, his Dumas-loving side identifying with their renegade romanticism and oppressed-status, and finding much humour in the vulgarity of Kemal's faux-Western innovations. In one scene he contrasts the authentic Turkish musical entertainment at a secret jihadi meeting with the "revolting crooning of some western barbarian" on a transistor radio in an adjacent building, and allows a Turkish woman over two pages to convince Swithin Destime, our hero, of the rightness of polygamy: "Monogamy might suit the West perhaps although even that was doubtful, and she produced statistics to hammer home her point."

.

It was a long speech and so admirably built up that Swithin had to admit the logic of the speaker's views - at least as far as the people she represented were concerned. If these Eastern women were content to share a man, as they had done for centuries, why should they not be allowed to continue to do so and, now that many of them were taking up careers there seemed a better reason than ever for two or more to divide the labours entailed by children and a home between them. Of course, few Western women, he realised, would be content to accept so short a sex life, that was the big snag, but apart from it and the question of Christian morality, the system, if adhered to, appeared wholesome when compared with the scandalous fraud and collusion which arise from the English divorce laws...

.

.Destime is almost swayed by the rhetoric of heroic idealist Reouf:

.

"Kemal did much for Turkey in the War and after, but he has sacrificed the soul of our nation for the material trappings of the West. We are not a European people and we never shall be. No wearing of bowler hats, jazz music and the co-education will ever make us so. We are Asiatics and the ways of our fathers which endured for centuries are those best-suited to our needs."

"Yet, you admit that sweeping reforms were long overdue."

"Truly - and they have now been carried out - but that could have been done without laws which force us to sin fifty times a day in the sight of Allah, or treaties which tie us down to the permanent acceptance of territorial limitations making us into a Third-Class State."

.

Largely because of the potential threat to British interests, however, Wheatley gradually navigates the reader into opposition, precisely at the point when political activism gives way to religious fundamentalism:

.

For one awful moment Swithin held his breath. The word 'Jehad' flamed through his brain with all its terrible possibilities. Of the patriotic ravings of young Reouf he had taken little stock but this was a very different business. It even far exceeded the scope of the determined internal revolution of which he had learned in the last ten minutes, for a Jehad meant the preaching of a Holy War. These people were not out only to destroy Kemal and reinstate the old law of the Koran but, with all the bitter zeal of blind fanaticism, they meant to carry their full programme into actual practice. It meant the certainty of another flare-up in the Balkans, their co-religionists would probably rise in sympathy and begin massacres of Europeans in India, Syria, Palestine, Egypt, Algeria and, taking into consideration the unstable state of things in Europe, perhaps even be the kindling spark leading to the supreme horror of a war to the death between fresh combinations of the Great Powers.

.

How chilling is that line: "... their co-religionists would probably rise in sympathy and begin massacres of Europeans in India..."? As Wheatley has one character note in typical style: "there's no reasoning with these birds..."

Here, though, Britishness is still a force to be measured:

.

The Daimler's engine purred and, with a superior glance at Malik, the cockney chauffeur let in the clutch. The Turk stood watching with impotent fury blazing in his eyes. He would cheerfully have given five years of his life to be able to draw his gun and haul Swithin out of the car at the point of it - but he dared not. A small silk Union Jack fluttered gaily from a slim staff on the Daimler's bonnet. No policeman - be he black, white, yellow, or brown, lays hands with impunity upon the property of His Britannic Majesty's accredited representatives the wide world over - and Malik knew it. Stirred by profound emotion he spat, while Swithin, no less stirred by the portentous meaning of that little flag, looked away quickly and lit a cigarette.

.

.

.As noted, our hero is one Swithin Destime, Wheatley's most delicious name for a hero since Black August's Kenyon Wensleydale. He's kicked out of the Guards when he comes to the aid of dishy Diana Duncannon at a dinner party, by punching a "garlic-eating bounder" pestering her on the lawn. When the bounder turns out to be Prince Ali of Turkey, a sensitive political situation can only be avoided by having Destime, and his fellow pugilist Peter Carew, resign their commissions. Later, however, Diana's father offers Destime a job at the Turkish depot of his tobacco company, so as to snoop undercover among the locals and discern if there is any truth to the rumour that some form of uprising in the offing, and if there is, what that might mean for Blighty.

Diana ("cool and lovely in an outrageously fashionable hat") is a slightly new kind of Wheatley heroine: not merely feisty and resourceful (as was customary in his books) but the controlling force, and coquettish to boot. She repeatedly makes a fool of Destime, who is still underestimating her to the very end. He, by contrast, is a pretty hopeless amateur, relying chiefly on luck, guesswork and fisticuffs: exactly like the literary heroes with whom Diana mockingly compares him.

And Wheatley being Wheatley, he can't resist making the comparisons explicit:

.

In his mind, he sought desperately for a way of escape, but he could think of nothing. Again Diana's taunt came back to him and he wondered miserably just what those gifted amateurs of fiction did when they had walked blithely into the arms of their enemies. Bulldog Drummond, he supposed, would have tackled the present situation with fantastic ease... Bulldog might not be exactly subtle, but at times he certainly possessed the advantage of being devastatingly heavy handed. Then there was that other fellow, an infinitely more dangerous gentleman adventurer, 'The Saint'. Swithin had followed his amazing prowess in many countries, through fifteen novels, and admired him greatly. The remarkable flow of cheerful badinage which he managed to sustain even in the most desperate situations was a joy to read, and his methods a perfect example of how matters should be handled in the present instance.

.

But Swithin is no Saint, and virtually every major suspense episode is motivated by him behaving foolishly:

.

He had failed - failed utterly from the very beginning. By not foreseeing that Tania's was such a likely post for the police to plant a spy he had given himself away to Kazdim through entrusting her with that letter. By failing to catch and warn Reouf of Kazdim's identity that night when they left the cafe together he felt that he had been largely responsible for the poor boy's death. By not troubling to take the most elementary precautions at his flat he had walked blindly into the arms of the enemy, then, when almost miraculously his life had been spared, he had been crazy enough to place himself in Ali's clutches, where the veriest tyro would at least have taken care to find out the name of the Military Governor of Constantinople before risking a visit to him - and now, by his supreme folly in asking Diana to meet him at the Tobacco Depot, he had given her away to Kazdim too.

He had failed, not only in carrying out his mission, which he realised now was a thing of comparatively small account, since it only concerned investing certain sums of money but, through his incompetence, new wars were to be sprung on an unsuspecting world and , above all - a thing far nearer home - that woman whom he had considered hard and selfish but who was brave and proud, and whom he now knew that he loved so that he would go down to hell itself to help her, was to be humiliated, befouled, broken and tortured, in body and spirit. His cup of bitterness brimmed and spilled over when he recalled his refusal to take her warning - that he had not the brain or nerve for the job he had taken on so arrogantly - and knew it to be true.

.

He does redeem himself, for sure, but thanks to a lot of luck.

.

.As for Kazdim, the Eunuch himself, he's the head of the secret police, and a clandestine Islamist, much given to tying his enemies' limbs together and dumping them in deep water.

I suppose Wheatley must have realised that after Mocata his readers would no longer accept a mere ruffian for a villain. Kazdim, therefore, is a real showstopper:

.

He was a tall man with immensely powerful shoulders but the effect of his height was minimized by his gigantic girth. He had the stomach of an elephant and would easily have turned the scale at twenty stone. His face was even more unusual than his body for apparently no neck supported it and it rose straight out of his shoulders like a vast inverted U. The eyes were tiny beads in that vast expanse of flesh and almost buried in folds of fat, the cheeks puffed out, yet withered like the skin of a last year's apple, and the mouth was an absurd pink rosebud set above a seemingly endless cascade of chins.

.

The book offers the best example yet of Wheatley's climax-upon-climax formula: knowing, perhaps, that he wasn't going to top Devil Rides Out conceptually (though the astral bodies put in a reappearance), he has gone all out to top each action climax with another. The book just doesn't want to stop, and there are times when you wonder if it ever will. But it works: the effect is neither counterproductively exhausting, nor ridiculous.

Especially notable here is how the secondary character of Peter is used to achieve this effect, since it shows a genuinely clever awareness of narrative structure. The character is present at the beginning, cleverly reintroduced halfway through, and then held in reserve for Wheatley's cleverest 'last dash' yet, stepping in to foul up the works after Destime's efforts, finally, appear to have succeeded.

Our heroes are saved, ultimately, by the timely intervention of Tania, ("attractive enough to have caught the eye of the most hardened misogynist"), Kazdim's gorgeous paid agent. Swithin gets the measure of her halfway through, but Peter falls hard and naive for her, and as soon as he is entrusted with the important government commission to which all Destime's efforts have been directed, he promptly makes an ass of himself and allows her to betray him as ordered.

But now, tormented by conscience, and driven mad with guilt and hatred after the death of her mother at Kazdim's hands, her (literally) insane bravery saves the day at the cost of her own life.

This is also something new for Wheatley: his first tragic heroine, inspired perhaps by Devil's Tanith, whom he had shockingly killed halfway through, only to wimp out and bring back to life a few chapters later. Tania, who resembles Tanith in more than just name (the unwilling servant of the principal villain, loved by a secondary male hero who wants to 'take her away from all of this', a refugee) gets no second chance, and her death is powerfully woven by Wheatley into the breakneck action climax.

Ultimately, Swithin, Diana and Peter foil the revolution, avert catastrophe, earn the undying loyalty of Kemal (the first example in Wheatley of a real-life figure with a speaking role) and save the British Empire - temporarily at least.

The book ends with an official proclamation from Kemal to his people, to which one can only add 'Amen':

.

Those followers of the Prophet who wish to continue the practice of their ancient faith are free to do so, as also are the Christians and the Jews. But let them beware how they attempt to tamper with the machinery of State. Religion and nationality are things apart.

.

If you hate Wheatley's style, good luck to you and there's no more to be said.

But if you do have a sweet tooth for this kind of thing, this is one of his most efficient displays yet.

No sign yet of autopilot.